Britain's Near-Intervention in the American Civil War

One of the most intriguing "what ifs" of the Civil War concerns how differently things might have gone if Britain had recognized the Confederacy, as fire-eater Robert Barnwell Rhett clearly hoped it would when he paid a visit to Robert Bunch, the British consul to Charleston, days before South Carolina passed its ordinance of secession.

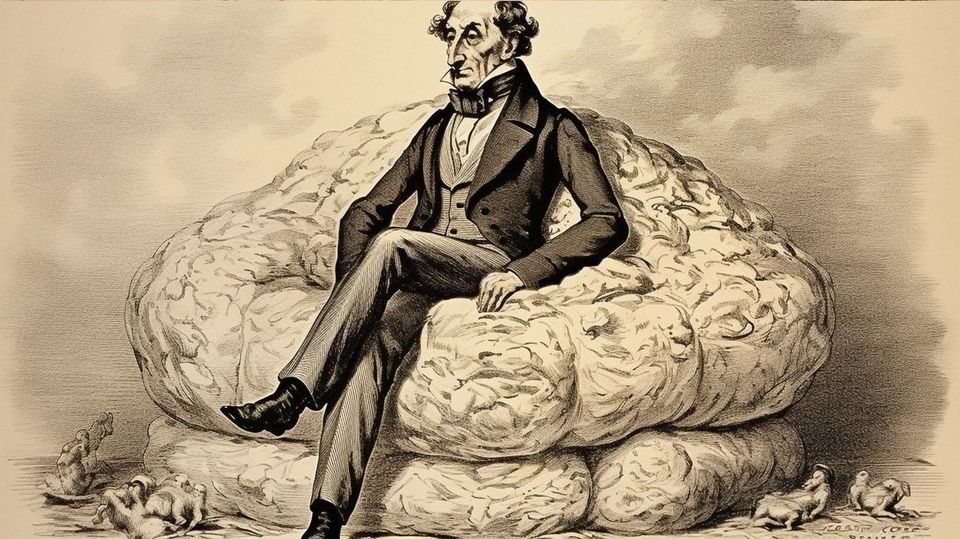

Rhett clearly erred in his cocky assumption, shared by many Confederates, that Britain so badly needed Southern cotton that it would have no choice but to side with the South, and he showed his lack of diplomatic acumen by flirting, in Bunch's presence, with the idea of reopening the African slave trade.

Ironically, just a few months later the provisional Confederate Congress, over Rhett's objections, enshrined the ban in the new constitution – something the United States hadn't even done. (Rhett's biographer William C. Davis shows that while Rhett treated his own slaves with relative kindness, he was so hypersensitive to criticisms of the peculiar institution that he saw the ban on the gruesome Middle Passage as a tacit admission that slavery was wrong. After decades of attacks by Northerners on Southern honor, now he saw the fledgling Confederacy casting its own aspersions.)

The constitutional ban was not enough to reassure the British, who suspected that the Confederacy's decentralized structure would make the ban unenforceable, as Christopher Dickey notes in Our Man in Charleston: Britain's Secret Agent in the Civil War South. Dickey also recounts how Bunch's dispatches ended up attracting the scrutiny and suspicion of U.S. Secretary of State William Seward and John A. Kennedy, the superintendent of New York City's Metropolitan Police, who incorrectly accused Bunch of being a "notorious secessionist" who "used his office for facilitating the transmission of treasonable correspondence." Diplomatic tensions over "the Bunch affair" led to the British government revoking his diplomatic credentials while keeping him in Charleston to keep sending reports nonetheless. Eventually his position became untenable and he was "reassigned to Cuba, where he sat on the joint commission adjudicating slave-trade cases. Subsequently he was posted to Bogotá, Columbia, where he became Her Majesty's minister plenipotentiary, the post he had wanted for many years."

Sheldon Vanauken, in his fascinating book The Glittering Illusion: English Sympathy for the Confederacy, describes how close the British came to backing the South. It did not have to make a decision early in the war, for bumper crops in 1859 and 1860 had left British warehouses stuffed with surplus fiber. And as Vanauken writes, fast-forwarding a couple of years:

In 1862 the Southerners were not defeated, and England had no thought that they ever would be; indeed, they looked very like winning, perhaps before the year was out. At the outbreak of the war England had proclaimed a proper neutrality whilst waiting to see whether the Union armies would in fact quickly destroy the rebellion of 'a few wicked conspirators'. But now in the late summer of 1862 Lee had won the great victory of the Seven Days, and in September Lee and Jackson brilliantly defeated the United States army at the old Manassas battlefield. The North, said The Times, was on the 'verge of ruin'.

As for the British government:

The question of recognition and mediation had in fact been turned over from the beginning: the Government ... were waiting for the right moment. Gladstone, a true Liberal, sympathized with the South on the grounds that it was struggling as an oppressed nationality. Palmerston was at once sympathetic to the South and hostile to the North. Even Russell, if not in favour of the Confederacy, had small sympathy with its enemies. Other members of the Cabinet, for various reasons, regarded the separation of the former regions as desirable. In September, 1862, the right moment came. The Federals had got a "very complete smashing" at the second battle of Manassas (or Bull Run); and General Lee then led the Army of Northern Virginia across the frontiers of the United States. Palmerston wrote to Russell that, if the Union suffered another great defeat, if Washington or Baltimore should fall, it would be time to mediate. ... Gladstone shook the country by implying unmistakably that recognition was at hand when he said, in the famous Newcastle speech, that Jefferson Davis had not only made an army and a navy but had made a nation. ...

It was, in fact, a favourable moment, the 'right moment', for, as Gladstone had observed in his Memorandum to the Cabinet: "fortunes have been placed for the moment in equilibrio by the failure of the main invasions on both sides". But the Cabinet had not made up its mind, despite Gladstone and the enthusiastic English reaction; Lord Palmerston hesitated, feeling that this was not the 'right moment'; Gladstone and Russell, who felt that it was, probably agreed that a better one would come along. But this was the moment of destiny; this was the flood tide of the Confederacy, and England's nearest approach to decisive action. The Government did not ever decide that there would be no action; they merely did not ever decide that it was time to act. They waited for the right moment – which was not to come again. And Parliament waited for the Ministry's need. And England waited upon the Parliament. And France waited to follow England.

In an epilogue, Vanauken indulges in a few pages of speculative fiction, writing an imaginary sketch by a 20th-century British historian showing how different the world might have looked if Britain had allied with the South, resulting in a Southern victory at Gettysburg, causing the U.S. government to yield "to the universal cry for peace" and capitulate:

It was an alliance destined to become even closer when the South became, somewhat later, a member of the British Commonwealth, and its President became Prime Minister, with a Royal Governor to open the Parliament at Richmond in the name of the Queen. ...

[One] result of that victory has been the firm establishment of the principle of self-determination, to which even the United States and Russia now give assent. An equally important result of the victory was, as the Confederate Commissioner to London, J.M. Mason – Sir James as he became – had promised, the gradual ending of slavery. It was in 1875 that the Southern Prime Minister, Lord Arlington – or, to use a more familiar designation, General Lee – announced that the several states had agreed that all slaves born after the last day of 1879 would be free; and the Confederacy thereupon embarked on the benign programme of slowly raising the Negro to the limits of his ability. A few years later the United States also emanicpated the small number of slaves in their territories. We can only be grateful that emancipation of the slaves in the south came about in this way and that the sinister Emancipation Proclamation of President Lincoln – an invitation to the slaves to rise against their masters, or more precisely their mistresses, since the men were with the army – had no effect. ...

One more result of the Allied victory at Gettysburg must not be neglected: the complete discrediting of that barbarism in warfare that marked the efforts of the Americans to subdue the Southerners – the barbarism of Generals Sherman and Sheridan and "Beast" Butler. It is to be hoped that no civilised nation will again make use of such methods. There is, indeed, reason to hope that no civilised nation will again resort to war of any sort. In the seventy-five years of world peace which have followed the Great War or One Year War of 1914-1915 when the Allies so completely defeated Germany – a victory, incidentally, that might not have been so swiftly but for the Confederate divisions under the second Marquess of Arlington – the Kaisers appear to have relinquished their dreams of militaristic glory.

Just how realistic Vanauken's "whatifery" was, of course, is anybody's guess. What's yours?