'Negrophobia' in the Antebellum North

Historian C. Vann Woodward wrote in his classic book The Strange Career of Jim Crow that one "of the strangest things about the career of Jim Crow was that the system was born in the North and reached an advanced age before moving South in force."

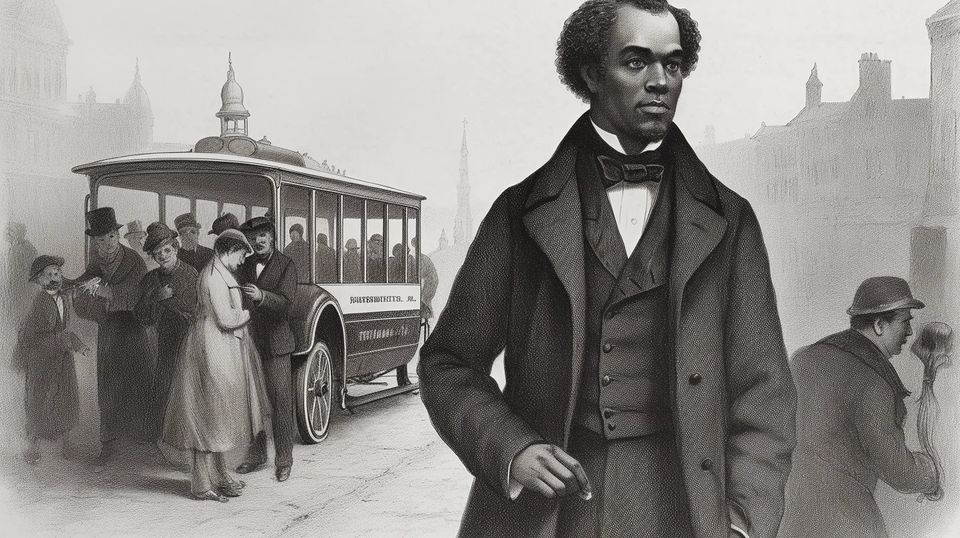

William Wells Brown, a runaway slave who became an internationally renowned antislavery crusader and literary figure, wrote about experiencing Northern Jim Crow, which he called "Negrophobia," firsthand upon returning to the United States from Europe, where he had dined with the literati and come and gone as he pleased. He got a stinging reminder of where he was when he tried to board a Philadelphia omnibus.

Brown's experience would be repeated, with variations, in the 20th century by black American writers like Richard Wright and James Baldwin who found Paris more hospitable than their homeland (although Baldwin noted that French Arabs were treated more like black Americans were in the United States).

Elaborating on Northern antebellum conditions for African Americans, Woodward wrote:

By 1830 slavery was virtually abolished by one means or another throughout the North, with only about 3500 Negroes remaining in bondage in the nominally free states. No sectional comparison of race relations should be made without full regard for this difference. The Northern free Negro enjoyed obvious advantages over the Southern slave. His freedom was circumscribed in many ways, as we shall see, but he could not be bought or sold, or separated from his family, or legally made to work without compensation. He was also to some extent free to agitate, organize, and petition to advance his cause and improve his lot.

For all that, the Northern Negro was made painfully and constantly aware that he lived in a society dedicated to the doctrine of white supremacy and Negro inferiority. The major political parties, whatever their position on slavery, vied with each other in their devotion to this doctrine, and extremely few politicians of importance dared question them. Their constituencies firmly believed that the Negroes were incapable of being assimilated politically, socially, or physically into white society. They made sure in numerous ways that the Negro understood his ‘place’ and that he was severely confined to it. One of these ways was segregation, and with the backing of legal and extra-legal codes, the system permeated all aspects of Negro life in the free states by 1860.

Leon F. Litwack, in his authoritative account, North of Slavery, describes the system in full development. ‘In virtually every phase of existence,’ he writes, ‘Negroes found themselves systematically separated from whites. They were either excluded from railway cars, omnibuses, stagecoaches, and steamboats or assigned to special “Jim Crow” sections; they sat, when permitted, in secluded and remote corners of theaters and lecture halls; they could not enter most hotels, restaurants, and resorts, except as servants; they prayed in “Negro pews” in the white churches, and if partaking of the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, they waited until the whites had been served the bread and wine. Moreover, they were often educated in segregated schools, punished in segregated prisons, nursed in segregated hospitals, and buried in segregated cemeteries.’

In very few instances were Negroes and other opponents of segregation able to make any progress against the system. Railroads in Massachusetts and schools in Boston eliminated Jim Crow before the Civil War. But there and elsewhere Negroes were often segregated in public accommodations and severely segregated in housing. Whites of South Boston boasted in 1847 that ‘not a single colored family’ lived among them. Boston had her ‘Nigger Hill’ and her ‘New Guinea,’ Cincinnati her ‘Little Africa,” and New York and Philadelphia their comparable ghettoes—for which Richmond, Charleston, New Orleans, and St. Louis had no counterparts. A Negro leader in Boston observed in 1860 that ‘it is five times as hard to get a house in a good location in Boston as in Philadelphia, and it is ten times as difficult for a colored mechanic to get work here as in Charleston.’

Generally speaking, the farther west the Negro went in the free states the harsher he found the proscription and segregation. Indiana, Illinois, and Oregon incorporated in their constitutions provisions restricting the admission of Negroes to their borders, and most states carved from the old Northwest Territory either barred Negroes in some degree or required that they post bond guaranteeing good behavior. Alexis de Tocqueville was amazed at the depth of racial bias he encountered in the North. ‘The prejudice of race,' he wrote, 'appears to be stronger in the states that have abolished slavery than in those where it still exists, and nowhere is it so intolerant as in those states where servitude has never been known.'

Racial discrimination in political and civil rights was the rule in the free states and any relaxation the exception. The advance of universal white manhood suffrage in the Jacksonian period had been accompanied by Negro disfranchisement. Only 6 per cent of the Northern Negroes lived in the five states —Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Vermont, Maine, and Rhode Island—that by 1860 permitted them to vote. The Negro’s rights were curtailed in the courts as well as at the polls. By custom or by law Negroes were excluded from jury service throughout the North. Only in Massachusetts, and there not until 1855, were they admitted as jurors. Five Western states prohibited Negro testimony in cases where a white man was a party. The ban against Negro jurors, witnesses, and judges, as well as the economic degradation of the race, help to explain the disproportionate numbers of Negroes in Northern prisons and the heavy limitations on the protection of Negro life, liberty, and property.

It's worth keeping this context in mind when thinking about Northern opposition to allowing slavery in the territories – one of the most divisive issues between the sections throughout the late 1840s and 1850s. Congressman David Wilmot of Pennsylvania, whose Wilmot Proviso sought to ban slavery in territory acquired in the Mexican-American War, was candid about wanting to keep the West for white men.

When Northerners like Theodore Parker railed against the "expansion" of slavery, what they were objecting to was its being spread thin over wider terrain, not to an increase in the number of enslaved people, since the African slave trade had been banned since 1808. (As we saw last week, there were Southern fanatics like Leonidas W. Spratt who wanted to to reopen the internationl slave trade, but their efforts went nowhere both before and after secession.)

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded.