Southerners Warily Follow a Copperhead's Moves

Historian Frank L. Klement wrote The Limits of Dissent: Clement L. Vallandigham and the Civil War during the Vietnam War, when it must have felt like a now-more-than-ever story to tell. But in the 1860s, writes Klement, antiwar agitators like Vallandigham weren't hippies, but conservatives who "recognized the revolution occurring within the Civil War, transforming the federal union into 'a new nation,' giving industry ascendancy over agriculture, extending rights to the black man, ending the upper Midwest's chance to play balance-of-power politics, and threatening civil rights and personal freedoms."

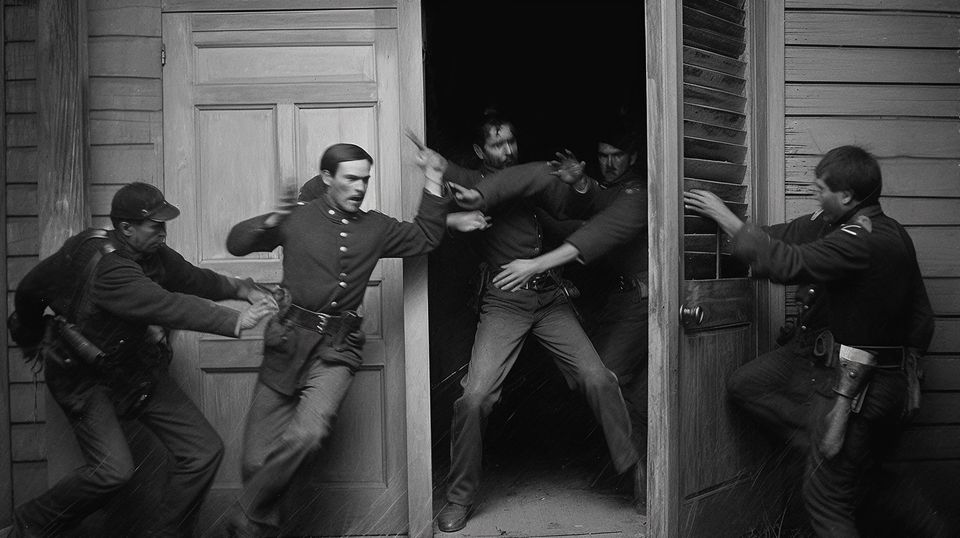

Thus it was with a sympathetic but wary eye that Virginia fire-eater Edmund Ruffin, who while long-haired was also no hippie, followed the moves of Vallandigham and other "malcontents" through the papers.

Here Ruffin, for all his fanaticism, shows himself to be a sophisticated follower of the news media of his time. As with the John Brown entries, he knows not to fully credit everything he reads, and he doesn't let his hopes color his interpretations of events. And his interpretation of Lincoln's political calculations was accurate, and shared by Vallandigham and the Confederate government. As the Southern diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut, wife of Confederate functionary James Chesnut Jr. wrote upon her husband's return after escorting Vallandigham to Wilmington, North Carolina to await passage on the blockade runner to Bermuda en (circuitous) route to Canada: "He kept dark about Vallandigham. I am sure we could not trust him to do us any good or to do the Yankees any harm. The Coriolanus business is played out."

(Notes Chesnut diary editor C. Vann Woodward in the footnote: "In Shakespeare's play, the exiled Roman Coriolanus joins Tullus, an enemy of Rome, in a war against the city.)

Although Valandigham sympathized with Southern aversion to New England's dominant stance toward other sections and had traveled to Harpers Ferry to interrogate Brown after his arrest, he no desire to play Coriolanus. Klement writes that when Vallandigham visited General Braxton Bragg's headquarters shortly after arriving in Tennessee, "the general congratulated the exhile upon his arrival in a 'land of liberty' and told his guest that he would find freedom of speech and conscience in Dixie. Vallandigham curtly denied that he sought citizenship or rights and freedom in Dixie, insisting that he was a prisoner of war."

It's not entirely clear where principle left off and politics began; Klement makes clear that Vallandigham hoped to score martyr points that would boost his Ohio gubernatorial run. But Chesnut was right that he meant the Yankees no harm.

Vallandigham pursued politics at a time when it was tough to be a Democrat in Ohio, where Republicans were ascendant. He lost more elections than he won and barely won the two terms in Congress he served. He ended up resuming his legal practice with great success, only to accidentally shoot himself while attempting to demonstrate how the alleged victim of a client he was defending had shot himself. He had grabbed the wrong gun by mistake. He died June 16, 1871, a few weeks shy of his 51st birthday.

See you next post. If you'd like to get these delivered to your inbox (for free), hit the subscribe button and enter your email address. You may need to check your spam folder for the confirmation email, but I'll never spam you or share your address. You'll just get these posts with the video embedded.